Saturday, November 15, 2003

U.S. soldiers who survive attacks in Iraq often face lasting injuries

The wounds of war

U.S. soldiers who survive attacks in Iraq often face lasting injuries

By John Simerman

CONTRA COSTA TIMES

The ambush came in darkness, as an Army convoy rolled past dirt fields 25 miles south of Baghdad.

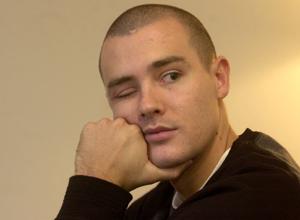

Through night-vision goggles, Pfc. Reed Rosenkranz of Pittsburg could make out rubble in the distance. He sat behind the driver in the lead Humvee, a radio pack strapped across his back. A heavy Kevlar vest shielded his torso -- but not his legs, not his arms, not his eyes.

The explosion sent the Humvee spinning. It ripped the goggles from his head. It tore him up.

"All it was was a flash of light, ears ringing and you've got wounds all over you," he said of the Oct. 6 blast that took his right eye, shot shrapnel through his limbs and killed two soldiers and an Iraqi interpreter in the same vehicle.

"They can't shoot worth the darnedest," said the 24-year-old private, who returned home last week. "The only thing they're getting us with is improvised explosive devices." (IEDs)

Now home on convalescent leave, he is among a rising count of U.S. troops wounded or killed in Iraq with powerful makeshift bombs. Fashioned from old ordnance, rigged with trip-wires or remote triggers, they are set off along U.S. troop routes with alarming frequency and brutal force, military officials say.

Roadside bombs have killed dozens of U.S. soldiers and caused a swelling number of severe wounds to arms, legs and other body parts left unprotected by helmets, flak vests and new "interceptor" body armor.

"There's no real 100 percent protection out here," said Sgt. Danny Martin, a U.S. military spokesman in Iraq. "When you rig three or four or five tank rounds together, it can create a rather large explosion."

Since President Bush on May 1 declared the end of major combat operations in Iraq, 1,416 soldiers have been wounded in action, compared to 551 prior to May 1, according to the Department of Defense. Of the 270 U.S. troop deaths attributed to hostilities in Iraq, 156 have come after May 1.

Many of the deaths and injuries were the result of roadside explosives, now "the most widely used weapon out here," said Martin. "They're extremely tough to find."

In October alone, IEDs killed 17 U.S. troops. Since Nov. 1, 11 more soldiers have been killed by IEDs or mines, according to Defense reports.

"It's a whole different war than the war that was going on before (May 1)," said Dr. Lynn Welling, a Navy captain who was attached to a shock trauma platoon in Iraq. "You're cruising around on a routine patrol and a car bomb goes off nearby. It's a terrorist fight right now."

Perhaps 70 percent of the wounds now are to extremities, said Welling. U.S. military medical staff have met greater success saving soldiers' lives than in past wars. In Korea, Vietnam and the first gulf war, about one in four wounded U.S. soldiers died. In this war, about one in eight die.

Welling credits better body armor, more soldiers wearing it, and a strategy to place better-equipped medical units closer to the action. Most battlefield deaths, he said, are from blood loss.

"We're getting the wounded back," he said.

As the toll rises, U.S. military hospital beds are filling with soldiers.

When Rosenkranz reached Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington a week after the blast, he saw many soldiers who lost eyes or limbs. According to the Army Medical Command, 52 U.S. soldiers wounded in Iraq have had one or more limbs amputated.

"I'm seeing guys with missing hands, with two hooks he'll have for the rest of his life. A lot of people lost eyes," said Rosenkranz. "I'd rather have a missing eye than a missing leg. I can still see with my left eye."

A shard of shrapnel, about a quarter-inch long, lodged in the back of his right eye. Doctors told him an infection in the blinded eye could creep over to the other eye. They removed the eyeball.

In two plastic bottles, he keeps the sharp chunks that ripped into his face, a wrist and both legs in al-Haswah. About five other pieces remain lodged deep in his leg. His muscles tighten around them. At some point, doctors told him, his body will reject them.

Now relaxing at home in Pittsburg with his wife, Allison, Rosenkranz will return to the East Coast next month for further treatment. The couple wed in January, five days before he left for basic training.

Rosenkranz counts himself lucky. A radio telephone operator, he usually sat behind the passenger seat, closer to where the bomb exploded, he said. On this ride, Lt. Richard Torres wanted the interpreter in that seat.

"I should've been sitting where he was," said Rosenkranz. "I definitely feel God was on my side."

Torres, Pfc. Kerry D. Scott and the interpreter died in the blast. The driver, an Army specialist, was the only other survivor. He also lost an eye -- the left one.

Rosenkranz still keeps his dark hair closely cropped. Drawn to military service after the Sept. 11 attacks, he wishes he could return to Iraq, to finish the job.

"I know my platoon needs me," he said. But with one eye, the young private is considered non-deployable. He seems resigned to a discharge and a Purple Heart.

He spent barely a month in Iraq -- a tour cut short, but long enough to see the rubble ahead.

"There's just tons of resistance over there," he said. "There's no way we can stop all of it. It's going to take a while."

Army Private First Class Reed Rosenkranz lost an eye and suffered many shrapnel wounds during an ambush south of Baghdad. (Susan Tripp Pollard/Contra Costa Times)

Ohio.com - Northeast Ohio's Home Page

|

U.S. soldiers who survive attacks in Iraq often face lasting injuries

By John Simerman

CONTRA COSTA TIMES

The ambush came in darkness, as an Army convoy rolled past dirt fields 25 miles south of Baghdad.

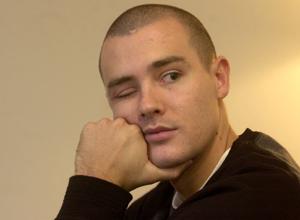

Through night-vision goggles, Pfc. Reed Rosenkranz of Pittsburg could make out rubble in the distance. He sat behind the driver in the lead Humvee, a radio pack strapped across his back. A heavy Kevlar vest shielded his torso -- but not his legs, not his arms, not his eyes.

The explosion sent the Humvee spinning. It ripped the goggles from his head. It tore him up.

"All it was was a flash of light, ears ringing and you've got wounds all over you," he said of the Oct. 6 blast that took his right eye, shot shrapnel through his limbs and killed two soldiers and an Iraqi interpreter in the same vehicle.

"They can't shoot worth the darnedest," said the 24-year-old private, who returned home last week. "The only thing they're getting us with is improvised explosive devices." (IEDs)

Now home on convalescent leave, he is among a rising count of U.S. troops wounded or killed in Iraq with powerful makeshift bombs. Fashioned from old ordnance, rigged with trip-wires or remote triggers, they are set off along U.S. troop routes with alarming frequency and brutal force, military officials say.

Roadside bombs have killed dozens of U.S. soldiers and caused a swelling number of severe wounds to arms, legs and other body parts left unprotected by helmets, flak vests and new "interceptor" body armor.

"There's no real 100 percent protection out here," said Sgt. Danny Martin, a U.S. military spokesman in Iraq. "When you rig three or four or five tank rounds together, it can create a rather large explosion."

Since President Bush on May 1 declared the end of major combat operations in Iraq, 1,416 soldiers have been wounded in action, compared to 551 prior to May 1, according to the Department of Defense. Of the 270 U.S. troop deaths attributed to hostilities in Iraq, 156 have come after May 1.

Many of the deaths and injuries were the result of roadside explosives, now "the most widely used weapon out here," said Martin. "They're extremely tough to find."

In October alone, IEDs killed 17 U.S. troops. Since Nov. 1, 11 more soldiers have been killed by IEDs or mines, according to Defense reports.

"It's a whole different war than the war that was going on before (May 1)," said Dr. Lynn Welling, a Navy captain who was attached to a shock trauma platoon in Iraq. "You're cruising around on a routine patrol and a car bomb goes off nearby. It's a terrorist fight right now."

Perhaps 70 percent of the wounds now are to extremities, said Welling. U.S. military medical staff have met greater success saving soldiers' lives than in past wars. In Korea, Vietnam and the first gulf war, about one in four wounded U.S. soldiers died. In this war, about one in eight die.

Welling credits better body armor, more soldiers wearing it, and a strategy to place better-equipped medical units closer to the action. Most battlefield deaths, he said, are from blood loss.

"We're getting the wounded back," he said.

As the toll rises, U.S. military hospital beds are filling with soldiers.

When Rosenkranz reached Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington a week after the blast, he saw many soldiers who lost eyes or limbs. According to the Army Medical Command, 52 U.S. soldiers wounded in Iraq have had one or more limbs amputated.

"I'm seeing guys with missing hands, with two hooks he'll have for the rest of his life. A lot of people lost eyes," said Rosenkranz. "I'd rather have a missing eye than a missing leg. I can still see with my left eye."

A shard of shrapnel, about a quarter-inch long, lodged in the back of his right eye. Doctors told him an infection in the blinded eye could creep over to the other eye. They removed the eyeball.

In two plastic bottles, he keeps the sharp chunks that ripped into his face, a wrist and both legs in al-Haswah. About five other pieces remain lodged deep in his leg. His muscles tighten around them. At some point, doctors told him, his body will reject them.

Now relaxing at home in Pittsburg with his wife, Allison, Rosenkranz will return to the East Coast next month for further treatment. The couple wed in January, five days before he left for basic training.

Rosenkranz counts himself lucky. A radio telephone operator, he usually sat behind the passenger seat, closer to where the bomb exploded, he said. On this ride, Lt. Richard Torres wanted the interpreter in that seat.

"I should've been sitting where he was," said Rosenkranz. "I definitely feel God was on my side."

Torres, Pfc. Kerry D. Scott and the interpreter died in the blast. The driver, an Army specialist, was the only other survivor. He also lost an eye -- the left one.

Rosenkranz still keeps his dark hair closely cropped. Drawn to military service after the Sept. 11 attacks, he wishes he could return to Iraq, to finish the job.

"I know my platoon needs me," he said. But with one eye, the young private is considered non-deployable. He seems resigned to a discharge and a Purple Heart.

He spent barely a month in Iraq -- a tour cut short, but long enough to see the rubble ahead.

"There's just tons of resistance over there," he said. "There's no way we can stop all of it. It's going to take a while."

Army Private First Class Reed Rosenkranz lost an eye and suffered many shrapnel wounds during an ambush south of Baghdad. (Susan Tripp Pollard/Contra Costa Times)

Ohio.com - Northeast Ohio's Home Page